High-Power, Gold-Plated Copper Pinholes

- Precision Pinholes in Gold-Plated Copper Foils

- Mounted in Copper and Aluminum Housings for Dissipating Heat

- Designed for High-Power Applications

- Pinhole Sizes from Ø5 μm to Ø500 μm

P100CBP

High-Power Gold-Plated Copper Pinhole, Ø100 µm

Pinholes can be mounted using the external SM1 threads on the rear.

An 8-32 (M4 x 0.7) tapped hole on the bottom of the housing allows for direct mouning to posts.

Front View

Rear View

Please Wait

| Apertures Selection Guide |

|---|

| Single Precision Pinholes |

| Circular in Stainless Steel Foils |

| Circular in Stainless Steel Foils, Vacuum Compatible |

| Circular in Gold-Plated Copper Foils |

| Circular in Gold-Plated Copper Foils, High-Power Housings |

| Circular in Tungsten Foils |

| Circular in Molybdenum Foils |

| Square in Stainless Steel Foils |

| Pinhole Kits |

| Pinhole Wheels |

| Manual |

| Motorized |

| Pinhole Spatial Filter |

| Slits |

| Annular Apertures |

| Alignment Tools |

Click to Enlarge

Figure 1.1 Under sustained illumination by a 52 W, 975 nm continuous-wave laser, our high-power pinhole housing keeps the mounted foil more than 30 °C cooler than the same foil mounted in the aluminum housing used for our PxCB gold-plated copper pinholes. See the Thermal Performance tab for more information.

Features

- Precision Pinholes in Gold-Plated Copper Foils with High-Power Housings

- Gold Plated (77% Reflectance @ 800 nm) on Front Face

- PVD Black Coating (10% - 12% Reflectance Within the Visible Wavelength Range) on Back Face

- Copper Insert Draws Heat Out of Foil, Prolonging Pinhole Life

- Pinhole Sizes from Ø5 μm to Ø500 μm

- Contact Tech Sales to Discuss Custom Options

Thorlabs' gold-plated copper precision pinholes mounted in high-power housings are designed to withstand high-power applications better than standard pinholes. These mounted precision pinholes should be used with the beam incident on the reflective gold-plated side to minimize absorption of light by the pinhole, keeping the temperature of the foil down. The copper insert and aluminum housing are designed to draw heat away from the foil, prolonging the life of the pinhole in high-power applications. Note that as pulse durations get shorter, the power necessary for laser ablation of the pinhole decreases.

Precision pinholes offer small optical apertures for applications such as alignment, beam conditioning, spatial filtering, and imaging. The pinholes offered here use copper foils with gold plating on the front face and a physical vapor deposition (PVD) black coating on the reverse. They are available with apertures from Ø5 µm to Ø500 µm and are mounted in high-power copper and black-anodized aluminum housings.

The housings are engraved with the pinhole Item # and the diameter of the pinhole. The pinhole foil and copper insert can be removed by unscrewing the SM05 retaining ring with the SPW603 Spanner Wrench; use care as the foil is very thin (50 µm). Gloves should be worn to avoid damaging the foils.

For many applications, such as holography, spatial intensity variations in the laser beam are unacceptable. Using precision pinholes in conjunction with positioning and focusing equipment such as our KT311(/M) Spatial Filter System creates a "noise" filter, effectively stripping variations in intensity out of a Gaussian beam. Please see the Tutorial tab for more information on spatial filters.

Precision Pinhole Options

Thorlabs' precision pinholes are available with an assortment of fabrication materials and coatings. The choice of a particular size and material should depend on the application. Low-power applications may benefit more from the absorbance of blackened stainless steel foils. High-power applications may need the high damage threshold and reflectance of gold-plated copper foils (available in both standard and high-power housings), the high melting point and lower reflectance of our tungsten foils, or the high melting point of our molybdenum foils paired with the low reflectance (4% @ 800 nm) of their black-coated front side. Please see the Foil Comparison and Graph tabs for more information.

In addition to single pinholes, Thorlabs also offers pinhole wheels that contain 16 radially-spaced pinholes that are lithographically etched onto a chrome-plated fused silica substrate. These wheels allow the user to test multiple pinhole sizes within a setup.

If you do not see what you need among our stock pinhole offerings, it is possible to special order pinholes that are fabricated from different substrate materials, have different pinhole sizes, incorporate multiple holes in one foil, or provide different pinhole configurations. Customized pinhole housings are also available. Please contact Tech Sales to discuss your specific needs.

Cleaning

The coatings on these foils can be irreversibly damaged by solvents. If light smudges or stains appear on the foil, remove them using a piece of lens tissue that has been dampened with isopropyl alcohol (IPA); for removing dust, a gentle stream of clean, dry air is recommended. Acetone, methanol, and deionized (DI) water should be avoided.

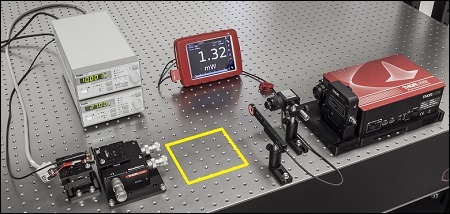

The thermal performance of a PxCBP high-power pinhole housing was compared to the aluminum housing used with our PxCB pinholes by measuring the temperature of both the foils and the exterior of the housings under sustained foil illumination. For these measurements, a blank, undrilled gold-plated copper foil was used to maximize the amount of light incident on the foil and the subsequent heating effect. For the PxCB pinhole, a PBCB Blank Gold-Plated Copper Foil was installed in an LMR1 mount on a Ø1/2" stainless steel post. For the PxCBP high-power pinhole, the same foil used in the PBCB mounted blank foil was installed into the PxCBP high-power housing mounted to a Ø1/2" stainless steel post. To measure the thermal performance, a 52 W, 975 nm continuous-wave laser was focused to a 1 mm 1/e2 diameter with an AL2520-B aspheric lens and directed onto the gold-plated side of the undrilled foil. Thermocouples were attached both to the foils and the exterior of the housings to measure the temperature rise caused by absorption of the laser beam. Note that the exterior temperature of the PxCB aluminum housing was measured at the exterior of the LMR1 mount. The PxCBP high-power pinhole housing was able to keep the foil more than 30 °C cooler than the PxCB pinhole housing in an LMR1 mount.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 2.2 Thermocouples were attached to the exterior of the housings to measure the temperature rise caused by a 52 W, 975 nm continuous-wave laser incident on the gold-plated side of a blank foil. Note that the exterior temperature of the PxCB aluminum housing was measured at the exterior of the LMR1 mount.

Click to Enlarge

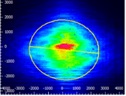

Figure 2.1 Thermocouples were attached to the gold-plated copper foils to measure the temperature rise caused by an incident 52 W continuous-wave laser at 975 nm.

Reflectance Graph

A reflectance graph for the gold-plated copper circular precision pinholes is presented here. The fronts of these gold-plated copper pinhole foils leave the gold coating exposed for minimal absorption of incident light. The back sides of these foils have a low-reflectance PVD black coating.

| Table 44A Precision Pinhole and Optical Slit Selection Guide | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Product | ||||

| Blackened Stainless Steel | Circular Precision Pinholes | ||||

| Square Precision Pinholes | |||||

| Optical Slits | |||||

| Tungsten Foil | Circular Precision Pinholes | ||||

| Stainless Steel with PVD Black Coating |

Circular Precision Pinholes | ||||

| Molybdenum Foil (Rear) and Absorptive Polymer Coating (Front) |

Circular Precision Pinholes | ||||

| Gold-Plated Copper Foil (Rear) and PVD Black Coating (Front) |

Circular Precision Pinholes | ||||

| Gold-Plated Copper Foil (Front) and PVD Black Coating (Rear) |

High-Power Circular Precision Pinholes |

||||

Precision Pinholes and Slits

Thorlabs offers precision pinholes with blackened stainless steel, gold-plated copper, tungsten, or molybdenum foils. Our pinholes with stainless steel foils are blackened on both sides for increased absorbance and are available from stock in circles from Ø1 µm to Ø9 mm and squares from 100 µm x 100 µm to 1 mm x 1 mm. Our stainless steel pinholes with a black PVD coating are vacuum compatible and available in 5 μm to 2 mm diameters. Our pinholes with gold-plated copper foils, plated with gold on one side and black PVD coated on the reverse, are available with pinhole diameters from 5 µm to 2 mm. High-power gold-plated copper foil pinholes are also available, with the gold-plated copper foil on the front face, and a PVD black coating on the rear. Our pinholes with tungsten foils are uncoated and available with pinhole diameters from 5 µm to 2 mm. Lastly, our pinholes with molybdenum foils have an absorptive polymer coating on the front sides and are available with pinhole diameters from 5 µm to 2 mm. We also offer slits in blackened stainless steel foils from stock with slit widths from 5 to 200 µm.

If you do not see what you need among our stock pinhole and slit offerings, it is also possible to special order pinholes and slits that are made with different foil materials, have different hole sizes and shapes, incorporate multiple holes in one foil, or provide different hole configurations. Please contact Tech Sales to discuss your specific needs. For more information on the properties of the bulk materials from which the pinholes are fabricated, see Table 44B.

Material Properties

Depending on the application, it can be important to consider the material properties of the pinhole or slit. The material used to construct the aperture can have varying levels of melting point, density, and thermal conductivity, as detailed in Table 44B.

| Table 44B Material Properties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | 300 Series Stainless Steela | Copperb | Tungsten | Molybdenumc |

| Melting Point | 1390 - 1450 °C | 1085 °C | 3422 °C | 2623 °C |

| Density | 8.03 g/cm3 | 8.96 g/cm3 | 19.25 g/cm3 | 10.28 g/cm3 |

| Brinell Hardness | 170 MPa | 878 MPa | 2570 MPa | 1500 MPa |

| Damage Thresholdd (10 ns Pulse, 1 kHz @ 355 nm) | 1.54 MW/mm2 | 4.82 MW/mm2 | 9.39 MW/mm2 | 6.34 MW/mm2 |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient | 16.2 (µm/m)/°C | 16.7 (µm/m)/°C | 4.5 (µm/m)/°C | 5.0 (µm/m)/°C |

| Specific Heat @ 20 °C | 485 J/(K*kg) | 385 J/(K*kg) | 134 J/(K*kg) | 250 J/(K*kg) |

| Thermal Conductivity | 16.2 W/(m*K) | 401 W/(m*K) | 173 W/(m*K) | 138 W/(m*K) |

| Thermal Diffusivity @ 300 K | 3.1 mm2/s | 111 mm2/s | 80 mm2/s | 54.3 mm2/s |

Reflectance

The reflectance of the foil material or coating affects performance in a variety of applications. Figure 44C shows a reflectance graph for all the materials and coatings that are offered with our circular and square precision pinholes, as well as our mounted optical slits. The raw reflectance data can be found here.

It is important to note that the front of the gold-plated copper foil circular precision pinholes have a low-reflectance PVD black coating. The rear of these pinholes leaves the gold-plated copper foil bare. This also occurs on the molybdenum foil circular precision pinholes, which have a low-reflectance absorptive polymer coating on the front and the molybdenum foil is left bare on the back.

Click to Enlarge

Click here for raw data.

Figure 44C Reflectance Comparison of Thorlabs' Foil Materials and Coatings

Principles of Spatial Filters

For many applications, such as holography, spatial intensity variations in the laser beam are unacceptable. Our KT311 spatial filter system is ideal for producing a clean Gaussian beam.

Figure 5.1 Spatial Filter System

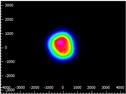

The input Gaussian beam has spatially varying intensity "noise". When a beam is focused by an aspheric lens, the input beam is transformed into a central Gaussian spot (on the optical axis) and side fringes, which represent the unwanted "noise" (see Figure 5.2). The radial position of the side fringes is proportional to the spatial frequency of the "noise".

Figure 5.2 Input Gaussian Beam

By centering a pinhole on a central Gaussian spot, the "clean" portion of the beam can pass while the "noise" fringes are blocked (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Clean Gaussian Beam

The diffraction-limited spot size at the 99% contour is given by Equation 1:

where λ = wavelength, ƒ=focal length and r = input beam radius at the 1/e2 point.

Choosing the Correct Optics and Pinhole for Your Spatial Filter System

The correct optics and pinhole for your application depend on the input wavelength, source beam diameter, and desired exit beam diameter.

For example, suppose that you are using a 650 nm diode laser source that has a diameter (1/e2) of 1.2 mm and want your beam exiting the spatial filter system to be about 4.4 mm in diameter. Based on these parameters, the C560TME-B mounted aspheric lens would be an appropriate choice for the input side of spatial filter system because it is designed for use at 650 nm, and its clear aperture measures 5.1 mm, which is large enough to accommodate the entire diameter of the laser source.

The equation for diffraction limited spot size at the 99% contour is given by Equation 1, and for this example, λ = (650 x 10-9 m), f = 13.86 mm for the C560TM-B, and r = 0.6 mm. Substitution yields

Diffraction-Limited Spot Size (650 nm source, Ø1.2 mm beam)

The pinhole should be chosen so that it is approximately 30% larger than D. If the pinhole is too small, the beam will be clipped, but if it is too large, more than the TEM00 mode will get through the pinhole. Therefore, for this example, the pinhole should ideally be 19.5 microns. Hence, we would recommend the mounted pinhole P20D, which has a pinhole size of 20 μm. Parameters that can be changed to alter the beam waist diameter, and thus the pinhole size required, include changing the input beam diameter and focal length of focusing lens. Decreasing the input beam diameter will increase the beam waist diameter. Using a longer focal length focusing lens will also increase the beam waist diameter.

Finally, we need to choose the optic on the output side of the spatial filter so that the collimated beam's diameter is the desired 4.4 mm. To determine the correct focal length for the lens, consider the following diagram in Figure 5.4, which is not drawn to scale. From the triangle on the left-hand side, the angle is determined to be approximately 2.48o. Using this same angle for the triangle on the right-hand side, the focal length for the plano-convex lens should be approximately 50 mm.

Figure 5.4 Beam Expansion Example

For this focal length, we recommend the LA1131-B plano-convex lens [with f = 50 mm at the design wavelength (λ = 633 nm), this is still a good approximation for f at the source wavelength (λ = 650 nm)].

Note: The beam expansion equals the focal length of the output side divided by the focal length of the input side.

For optimal performance, a large-diameter aspheric lens can be used in place of a plano-convex lens if the necessary focal length on the output side is 20 mm (see AL2520-A, AL2520-B, AL2520-C). These lenses are 25 mm in diameter and can be held in place using the supplied SM1RR Retaining Ring.

| Table 6.1 Damage Threshold Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Item # | Damage Thresholda |

| PxCBP, PxHCB, PxCB | 5 x 105 W/mm2, 75 ns Pulse @ 700 nm 1 x 106 W/mm2, 10 ns Pulse @ 700 nm 10 W/mm2, CW @ 10.6 µm |

Damage Threshold Data for Thorlabs' Gold-Plated Copper Pinholes

The specifications in Table 6.1 are measured data for Thorlabs' high-power gold-plated copper pinholes.

Laser Induced Damage Threshold Tutorial

The following is a general overview of how laser induced damage thresholds are measured and how the values may be utilized in determining the appropriateness of an optic for a given application. When choosing optics, it is important to understand the Laser Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) of the optics being used. The LIDT for an optic greatly depends on the type of laser you are using. Continuous wave (CW) lasers typically cause damage from thermal effects (absorption either in the coating or in the substrate). Pulsed lasers, on the other hand, often strip electrons from the lattice structure of an optic before causing thermal damage. Note that the guideline presented here assumes room temperature operation and optics in new condition (i.e., within scratch-dig spec, surface free of contamination, etc.). Because dust or other particles on the surface of an optic can cause damage at lower thresholds, we recommend keeping surfaces clean and free of debris. For more information on cleaning optics, please see our Optics Cleaning tutorial.

Testing Method

Thorlabs' LIDT testing is done in compliance with ISO/DIS 11254 and ISO 21254 specifications.

First, a low-power/energy beam is directed to the optic under test. The optic is exposed in 10 locations to this laser beam for 30 seconds (CW) or for a number of pulses (pulse repetition frequency specified). After exposure, the optic is examined by a microscope (~100X magnification) for any visible damage. The number of locations that are damaged at a particular power/energy level is recorded. Next, the power/energy is either increased or decreased and the optic is exposed at 10 new locations. This process is repeated until damage is observed. The damage threshold is then assigned to be the highest power/energy that the optic can withstand without causing damage. A histogram such as that shown in Figure 37B represents the testing of one BB1-E02 mirror.

Figure 37A This photograph shows a protected aluminum-coated mirror after LIDT testing. In this particular test, it handled 0.43 J/cm2 (1064 nm, 10 ns pulse, 10 Hz, Ø1.000 mm) before damage.

Figure 37B Example Exposure Histogram used to Determine the LIDT of

| Table 37C Example Test Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluence | # of Tested Locations | Locations with Damage | Locations Without Damage |

| 1.50 J/cm2 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| 1.75 J/cm2 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| 2.00 J/cm2 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| 2.25 J/cm2 | 10 | 1 | 9 |

| 3.00 J/cm2 | 10 | 1 | 9 |

| 5.00 J/cm2 | 10 | 9 | 1 |

According to the test, the damage threshold of the mirror was 2.00 J/cm2 (532 nm, 10 ns pulse, 10 Hz, Ø0.803 mm). Please keep in mind that these tests are performed on clean optics, as dirt and contamination can significantly lower the damage threshold of a component. While the test results are only representative of one coating run, Thorlabs specifies damage threshold values that account for coating variances.

Continuous Wave and Long-Pulse Lasers

When an optic is damaged by a continuous wave (CW) laser, it is usually due to the melting of the surface as a result of absorbing the laser's energy or damage to the optical coating (antireflection) [1]. Pulsed lasers with pulse lengths longer than 1 µs can be treated as CW lasers for LIDT discussions.

When pulse lengths are between 1 ns and 1 µs, laser-induced damage can occur either because of absorption or a dielectric breakdown (therefore, a user must check both CW and pulsed LIDT). Absorption is either due to an intrinsic property of the optic or due to surface irregularities; thus LIDT values are only valid for optics meeting or exceeding the surface quality specifications given by a manufacturer. While many optics can handle high power CW lasers, cemented (e.g., achromatic doublets) or highly absorptive (e.g., ND filters) optics tend to have lower CW damage thresholds. These lower thresholds are due to absorption or scattering in the cement or metal coating.

Figure 37D LIDT in linear power density vs. pulse length and spot size. For long pulses to CW, linear power density becomes a constant with spot size. This graph was obtained from [1].

Figure 37E Intensity Distribution of Uniform and Gaussian Beam Profiles

Pulsed lasers with high pulse repetition frequencies (PRF) may behave similarly to CW beams. Unfortunately, this is highly dependent on factors such as absorption and thermal diffusivity, so there is no reliable method for determining when a high PRF laser will damage an optic due to thermal effects. For beams with a high PRF both the average and peak powers must be compared to the equivalent CW power. Additionally, for highly transparent materials, there is little to no drop in the LIDT with increasing PRF.

In order to use the specified CW damage threshold of an optic, it is necessary to know the following:

- Wavelength of your laser

- Beam diameter of your beam (1/e2)

- Approximate intensity profile of your beam (e.g., Gaussian)

- Linear power density of your beam (total power divided by 1/e2 beam diameter)

Thorlabs expresses LIDT for CW lasers as a linear power density measured in W/cm. In this regime, the LIDT given as a linear power density can be applied to any beam diameter; one does not need to compute an adjusted LIDT to adjust for changes in spot size, as demonstrated in Figure 37D. Average linear power density can be calculated using this equation.

This calculation assumes a uniform beam intensity profile. You must now consider hotspots in the beam or other non-uniform intensity profiles and roughly calculate a maximum power density. For reference, a Gaussian beam typically has a maximum power density that is twice that of the uniform beam (see Figure 37E).

Now compare the maximum power density to that which is specified as the LIDT for the optic. If the optic was tested at a wavelength other than your operating wavelength, the damage threshold must be scaled appropriately. A good rule of thumb is that the damage threshold has a linear relationship with wavelength such that as you move to shorter wavelengths, the damage threshold decreases (i.e., a LIDT of 10 W/cm at 1310 nm scales to 5 W/cm at 655 nm):

While this rule of thumb provides a general trend, it is not a quantitative analysis of LIDT vs wavelength. In CW applications, for instance, damage scales more strongly with absorption in the coating and substrate, which does not necessarily scale well with wavelength. While the above procedure provides a good rule of thumb for LIDT values, please contact Tech Support if your wavelength is different from the specified LIDT wavelength. If your power density is less than the adjusted LIDT of the optic, then the optic should work for your application.

Please note that we have a buffer built in between the specified damage thresholds online and the tests which we have done, which accommodates variation between batches. Upon request, we can provide individual test information and a testing certificate. The damage analysis will be carried out on a similar optic (customer's optic will not be damaged). Testing may result in additional costs or lead times. Contact Tech Support for more information.

Pulsed Lasers

As previously stated, pulsed lasers typically induce a different type of damage to the optic than CW lasers. Pulsed lasers often do not heat the optic enough to damage it; instead, pulsed lasers produce strong electric fields capable of inducing dielectric breakdown in the material. Unfortunately, it can be very difficult to compare the LIDT specification of an optic to your laser. There are multiple regimes in which a pulsed laser can damage an optic and this is based on the laser's pulse length. The highlighted columns in Table 37F outline the relevant pulse lengths for our specified LIDT values.

Pulses shorter than 10-9 s cannot be compared to our specified LIDT values with much reliability. In this ultra-short-pulse regime various mechanics, such as multiphoton-avalanche ionization, take over as the predominate damage mechanism [2]. In contrast, pulses between 10-7 s and 10-4 s may cause damage to an optic either because of dielectric breakdown or thermal effects. This means that both CW and pulsed damage thresholds must be compared to the laser beam to determine whether the optic is suitable for your application.

| Table 37F Laser Induced Damage Regimes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse Duration | t < 10-9 s | 10-9 < t < 10-7 s | 10-7 < t < 10-4 s | t > 10-4 s |

| Damage Mechanism | Avalanche Ionization | Dielectric Breakdown | Dielectric Breakdown or Thermal | Thermal |

| Relevant Damage Specification | No Comparison (See Above) | Pulsed | Pulsed and CW | CW |

When comparing an LIDT specified for a pulsed laser to your laser, it is essential to know the following:

Figure 37G LIDT in energy density vs. pulse length and spot size. For short pulses, energy density becomes a constant with spot size. This graph was obtained from [1].

- Wavelength of your laser

- Energy density of your beam (total energy divided by 1/e2 area)

- Pulse length of your laser

- Pulse repetition frequency (prf) of your laser

- Beam diameter of your laser (1/e2 )

- Approximate intensity profile of your beam (e.g., Gaussian)

The energy density of your beam should be calculated in terms of J/cm2. Figure 37G shows why expressing the LIDT as an energy density provides the best metric for short pulse sources. In this regime, the LIDT given as an energy density can be applied to any beam diameter; one does not need to compute an adjusted LIDT to adjust for changes in spot size. This calculation assumes a uniform beam intensity profile. You must now adjust this energy density to account for hotspots or other nonuniform intensity profiles and roughly calculate a maximum energy density. For reference a Gaussian beam typically has a maximum energy density that is twice that of the 1/e2 beam.

Now compare the maximum energy density to that which is specified as the LIDT for the optic. If the optic was tested at a wavelength other than your operating wavelength, the damage threshold must be scaled appropriately [3]. A good rule of thumb is that the damage threshold has an inverse square root relationship with wavelength such that as you move to shorter wavelengths, the damage threshold decreases (i.e., a LIDT of 1 J/cm2 at 1064 nm scales to 0.7 J/cm2 at 532 nm):

You now have a wavelength-adjusted energy density, which you will use in the following step.

Beam diameter is also important to know when comparing damage thresholds. While the LIDT, when expressed in units of J/cm², scales independently of spot size; large beam sizes are more likely to illuminate a larger number of defects which can lead to greater variances in the LIDT [4]. For data presented here, a <1 mm beam size was used to measure the LIDT. For beams sizes greater than 5 mm, the LIDT (J/cm2) will not scale independently of beam diameter due to the larger size beam exposing more defects.

The pulse length must now be compensated for. The longer the pulse duration, the more energy the optic can handle. For pulse widths between 1 - 100 ns, an approximation is as follows:

Use this formula to calculate the Adjusted LIDT for an optic based on your pulse length. If your maximum energy density is less than this adjusted LIDT maximum energy density, then the optic should be suitable for your application. Keep in mind that this calculation is only used for pulses between 10-9 s and 10-7 s. For pulses between 10-7 s and 10-4 s, the CW LIDT must also be checked before deeming the optic appropriate for your application.

Please note that we have a buffer built in between the specified damage thresholds online and the tests which we have done, which accommodates variation between batches. Upon request, we can provide individual test information and a testing certificate. Contact Tech Support for more information.

[1] R. M. Wood, Optics and Laser Tech. 29, 517 (1998).

[2] Roger M. Wood, Laser-Induced Damage of Optical Materials (Institute of Physics Publishing, Philadelphia, PA, 2003).

[3] C. W. Carr et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 127402 (2003).

[4] N. Bloembergen, Appl. Opt. 12, 661 (1973).

In order to illustrate the process of determining whether a given laser system will damage an optic, a number of example calculations of laser induced damage threshold are given below. For assistance with performing similar calculations, we provide a spreadsheet calculator that can be downloaded by clicking the LIDT Calculator button. To use the calculator, enter the specified LIDT value of the optic under consideration and the relevant parameters of your laser system in the green boxes. The spreadsheet will then calculate a linear power density for CW and pulsed systems, as well as an energy density value for pulsed systems. These values are used to calculate adjusted, scaled LIDT values for the optics based on accepted scaling laws. This calculator assumes a Gaussian beam profile, so a correction factor must be introduced for other beam shapes (uniform, etc.). The LIDT scaling laws are determined from empirical relationships; their accuracy is not guaranteed. Remember that absorption by optics or coatings can significantly reduce LIDT in some spectral regions. These LIDT values are not valid for ultrashort pulses less than one nanosecond in duration.

Figure 71A A Gaussian beam profile has about twice the maximum intensity of a uniform beam profile.

CW Laser Example

Suppose that a CW laser system at 1319 nm produces a 0.5 W Gaussian beam that has a 1/e2 diameter of 10 mm. A naive calculation of the average linear power density of this beam would yield a value of 0.5 W/cm, given by the total power divided by the beam diameter:

However, the maximum power density of a Gaussian beam is about twice the maximum power density of a uniform beam, as shown in Figure 71A. Therefore, a more accurate determination of the maximum linear power density of the system is 1 W/cm.

An AC127-030-C achromatic doublet lens has a specified CW LIDT of 350 W/cm, as tested at 1550 nm. CW damage threshold values typically scale directly with the wavelength of the laser source, so this yields an adjusted LIDT value:

The adjusted LIDT value of 350 W/cm x (1319 nm / 1550 nm) = 298 W/cm is significantly higher than the calculated maximum linear power density of the laser system, so it would be safe to use this doublet lens for this application.

Pulsed Nanosecond Laser Example: Scaling for Different Pulse Durations

Suppose that a pulsed Nd:YAG laser system is frequency tripled to produce a 10 Hz output, consisting of 2 ns output pulses at 355 nm, each with 1 J of energy, in a Gaussian beam with a 1.9 cm beam diameter (1/e2). The average energy density of each pulse is found by dividing the pulse energy by the beam area:

As described above, the maximum energy density of a Gaussian beam is about twice the average energy density. So, the maximum energy density of this beam is ~0.7 J/cm2.

The energy density of the beam can be compared to the LIDT values of 1 J/cm2 and 3.5 J/cm2 for a BB1-E01 broadband dielectric mirror and an NB1-K08 Nd:YAG laser line mirror, respectively. Both of these LIDT values, while measured at 355 nm, were determined with a 10 ns pulsed laser at 10 Hz. Therefore, an adjustment must be applied for the shorter pulse duration of the system under consideration. As described on the previous tab, LIDT values in the nanosecond pulse regime scale with the square root of the laser pulse duration:

This adjustment factor results in LIDT values of 0.45 J/cm2 for the BB1-E01 broadband mirror and 1.6 J/cm2 for the Nd:YAG laser line mirror, which are to be compared with the 0.7 J/cm2 maximum energy density of the beam. While the broadband mirror would likely be damaged by the laser, the more specialized laser line mirror is appropriate for use with this system.

Pulsed Nanosecond Laser Example: Scaling for Different Wavelengths

Suppose that a pulsed laser system emits 10 ns pulses at 2.5 Hz, each with 100 mJ of energy at 1064 nm in a 16 mm diameter beam (1/e2) that must be attenuated with a neutral density filter. For a Gaussian output, these specifications result in a maximum energy density of 0.1 J/cm2. The damage threshold of an NDUV10A Ø25 mm, OD 1.0, reflective neutral density filter is 0.05 J/cm2 for 10 ns pulses at 355 nm, while the damage threshold of the similar NE10A absorptive filter is 10 J/cm2 for 10 ns pulses at 532 nm. As described on the previous tab, the LIDT value of an optic scales with the square root of the wavelength in the nanosecond pulse regime:

This scaling gives adjusted LIDT values of 0.08 J/cm2 for the reflective filter and 14 J/cm2 for the absorptive filter. In this case, the absorptive filter is the best choice in order to avoid optical damage.

Pulsed Microsecond Laser Example

Consider a laser system that produces 1 µs pulses, each containing 150 µJ of energy at a repetition rate of 50 kHz, resulting in a relatively high duty cycle of 5%. This system falls somewhere between the regimes of CW and pulsed laser induced damage, and could potentially damage an optic by mechanisms associated with either regime. As a result, both CW and pulsed LIDT values must be compared to the properties of the laser system to ensure safe operation.

If this relatively long-pulse laser emits a Gaussian 12.7 mm diameter beam (1/e2) at 980 nm, then the resulting output has a linear power density of 5.9 W/cm and an energy density of 1.2 x 10-4 J/cm2 per pulse. This can be compared to the LIDT values for a WPQ10E-980 polymer zero-order quarter-wave plate, which are 5 W/cm for CW radiation at 810 nm and 5 J/cm2 for a 10 ns pulse at 810 nm. As before, the CW LIDT of the optic scales linearly with the laser wavelength, resulting in an adjusted CW value of 6 W/cm at 980 nm. On the other hand, the pulsed LIDT scales with the square root of the laser wavelength and the square root of the pulse duration, resulting in an adjusted value of 55 J/cm2 for a 1 µs pulse at 980 nm. The pulsed LIDT of the optic is significantly greater than the energy density of the laser pulse, so individual pulses will not damage the wave plate. However, the large average linear power density of the laser system may cause thermal damage to the optic, much like a high-power CW beam.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 168A The beam circularization systems were placed in the area of the experimental setup highlighted by the yellow rectangle.

Comparison of Circularization Techniques for Elliptical Beams

Edge-emitting laser diodes emit elliptical beams as a consequence of the rectangular cross sections of their emission apertures. The component of the beam corresponding to the narrower dimension of the aperture has a greater divergence angle than the orthogonal beam component. As one component diverges more rapidly than the other, the beam shape is elliptical rather than circular.

Elliptical beam shapes can be undesirable, as the spot size of the focused beam is larger than if the beam were circular, and as larger spot sizes have lower irradiances (power per area). Techniques for circularizing an elliptical beam include those based on a pair of cylindrical lenses, an anamorphic prism pair, or a spatial filter. This work investigated all three approaches. The characteristics of the circularized beams were evaluated by performing M2 measurements, wavefront measurements, and measuring the transmitted power.

While it was demonstrated that each circularization technique improves the circularity of the elliptical input beam, each technique was shown to provide a different balance of circularization, beam quality, and transmitted power. The results of this work, which are documented in this Lab Fact, indicate that an application's specific requirements will determine which is the best circularization technique to choose.

Experimental Design and Setup

The experimental setup is shown in Figure 168A. The elliptically-shaped, collimated beam of a temperature-stabilized 670 nm laser diode was input to each of our circularization systems shown in Figures 168B through 168D. Collimation results in a low-divergence beam, but it does not affect the beam shape. Each system was based on one of the following:

- LJ1874L2-A and LJ1638L1-A Plano-Convex Convex Cylindrical Lenses (Figure 168B)

- PS873-A Unmounted Anamorphic Prism Pair (Figure 168C)

- Previous Generation KT310 Spatial Filter System with P5S Ø5 µm Pinhole (Figure 168D)

The beam circularization systems, shown in Figures 168B through 168D, were placed, one at a time, in the vacant spot in the setup highlighted by the yellow rectangle. With this arrangement, it was possible to use the same experimental conditions when evaluating each circularization technique, which allowed the performance of each to be directly compared with the others. This experimental constraint required the use of fixturing that was not optimally compact, as well as the use of an unmounted anamorphic prism pair, instead of a more convenient mounted and pre-aligned anamorphic prism pair.

The characteristics of the beams output by the different circularization systems were evaluated by making measurements using a power meter, a wavefront sensor, and an M2 system. In the image of the experimental setup shown in Figure 168A, all of these systems are shown on the right side of the optical table for illustrative purposes; they were used one at a time. The power meter was used to determine how much the beam circularization system attenuated the intensity of the input laser beam. The wavefront sensor provided a way to measure the aberrations of the output beam. The M2 system measurement describes the resemblance of the output beam to a Gaussian beam. Ideally, the circularization systems would not attenuate or aberrate the laser beam, and they would output a perfectly Gaussian beam.

Edge-emitting laser diodes also emit astigmatic beams, and it can be desirable to force the displaced focal points of the orthogonal beam components to overlap. Of the three circularization techniques investigated in this work, only the cylindrical lens pair can also compensate for astigmatism. The displacement between the focal spots of the orthogonal beam components were measured for each circularization technique. In the case of the cylindrical lens pair, their configuration was tuned to minimize the astigmatism in the laser beam. The astigmatism was reported as a normalized quantity.

Experimental Results

The experimental results are summarized in Table 168E, in which the green cells identify the best result in each category. Each circularization approach has its benefits. The best circularization technique for an application is determined by the system’s requirements for beam quality, transmitted optical power, and setup constraints.

Spatial filtering significantly improved the circularity and quality of the beam, but the beam had low transmitted power. The cylindrical lens pair provided a well-circularized beam and balanced circularization and beam quality with transmitted power. In addition, the cylindrical lens pair compensated for much of the beam's astigmatism. The circularity of the beam provided by the anamorphic prism pair compared well to that of the cylindrical lens pair. The beam output from the prisms had better M2 values and less wavefront error than the cylindrical lenses, but the transmitted power was lower.

| Table 168E Experimental Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Beam Intensity Profile | Circularitya | M2 Values | RMS Wavefront | Transmitted Power | Normalized Astigmatismb |

| Collimated Source Output (No Circularization Technique) |

Click to Enlarge Scale in Microns |

0.36 | Y Axis: 1.63 |

0.17 | Not Applicable | 0.67 |

| Cylindrical Lens Pair |  Click to Enlarge Scale in Microns |

0.84 | X Axis: 1.90 Y Axis: 1.93 |

0.30 | 91% | 0.06 |

| Anamorphic Prism Pair |

Click to Enlarge Scale in Microns |

0.82 | X Axis: 1.60 Y Axis: 1.46 |

0.16 | 80% | 1.25 |

| Spatial Filter |  Click to Enlarge Scale in Microns |

0.93 | X Axis: 1.05 Y Axis: 1.10 |

0.10 | 34% | 0.36 |

Components used in each circularization system were chosen to allow the same experimental setup be used for all experiments. This had the desired effect of allowing the results of all circularization techniques to be directly compared; however, optimizing the setup for a circularization technique could have improved its performance. The mounts used for the collimating lens and the anamorphic prism pair enabled easy manipulation and integration into this experimental system. It is possible that using smaller mounts would improve results by allowing the members of each pair to be more precisely positioned with respect to one another. In addition, using made-to-order cylindrical lenses with customized focal lengths may have improved the results of the cylindrical lens pair circularization system. All results may have been affected by the use of the beam profiler software algorithm to determine the beam radii used in the circularity calculation.

Additional Information

Some information describing selection and configuration procedures for several components used in this experimental work can be accessed by clicking the following hyperlinks:

| Posted Comments: | |

| No Comments Posted |

| Apertures Selection Guide | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aperture Type | Representative Image (Click to Enlarge) |

Description | Aperture Sizes Available from Stocka |

| Single Precision Pinholesa |

|

Circular Pinholes in Stainless Steel Foils | Ø1 µm to Ø9 mm |

|

Circular Pinholes in Stainless Steel Foils, Vacuum Compatible |

Ø5 µm to Ø2 mm | |

|

Circular Pinholes in Gold-Plated Copper Foils | Ø5 µm to Ø2 mm | |

|

Circular Pinholes in Gold-Plated Copper Foils with High-Power Housings |

Ø5 µm to Ø500 µm | |

|

Circular Pinholes in Tungsten Foils | Ø5 µm to Ø2 mm | |

|

Circular Pinholes in Molybdenum Foils | Ø5 µm to Ø2 mm | |

|

Square Pinholes in Stainless Steel Foils | 100 to 1000 µm Square | |

| Slitsa |  |

Slits in Stainless Steel Foils | 3 mm Slit Lengths: 5 to 500 µm Widths 10 mm Slit Lengths: 20 to 500 µm Widths |

|

Double Slits in Stainless Steel Foils | 3 mm Slit Lengths with 40, 50, or 100 µm Widths, Spacing of 3X or 6X the Slit Width |

|

| Half-Apertures |  |

Mounted, Half-Aperture Foils | Half-Apertures for Knife-Edge Scan Measurements |

| Annular Apertures |  |

Annular Aperture Obstruction Targets on Quartz Substrates with Chrome Masks |

Ø1 mm Apertures with ε Ratiosb from 0.05 to 0.85 Ø2 mm Aperture with ε Ratiob of 0.85 |

| Pinhole Wheels |  |

Manual, Mounted, Chrome-Plated Glass Disks with Lithographically Etched Pinholes |

Each Disk has 16 Pinholes from Ø25 µm to Ø2 mm and Four Annular Apertures (Ø100 µm Hole, 50 µm Obstruction) |

|

Motorized Pinhole Wheels with Chrome-Plated Glass Disks with Lithographically Etched Pinholes |

Each Disk has 16 Pinholes from Ø25 µm to Ø2 mm and Four Annular Apertures (Ø100 µm Hole, 50 µm Obstruction) |

|

| Pinhole Kits |  |

Stainless Steel Precision Pinhole Kits | Kits of Ten Circular Pinholes in Stainless Steel Foils Covering Ø5 µm to Ø9 mm |

| Item # | Pinhole Diameter | Diameter Tolerance | Circularitya | Foil Thickness | Foil Material | Damage Thresholdb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P5CBP(/M) | 5 µm | ±1 µm | ≥85% | 50 µm | Copper, Gold Plated on Front Side, Black PVD Coated on Back Side |

5 x 105 W/mm2, 75 ns Pulse @ 700 nm 1 x 106 W/mm2, 10 ns Pulse @ 700 nm 10 W/mm2, CW @ 10.6 μm |

| P10CBP(/M) | 10 µm | |||||

| P15CBP(/M) | 15 µm | ±1.5 µm | ||||

| P20CBP(/M) | 20 µm | ±2 µm | ≥90% | |||

| P25CBP(/M) | 25 µm | |||||

| P50CBP(/M) | 50 µm | ±3 µm | ||||

| P100CBP(/M) | 100 µm | ±4 µm | ≥95% | |||

| P200CBP(/M) | 200 µm | ±6 µm | ||||

| P500CBP(/M) | 500 µm | ±10 µm |

Products Home

Products Home

Zoom

Zoom High-Power Precision Pinholes

High-Power Precision Pinholes